Sanctum Carnis: Richard Nadler’s Flesh-Liturgy of Labor, Luxury, and Machine

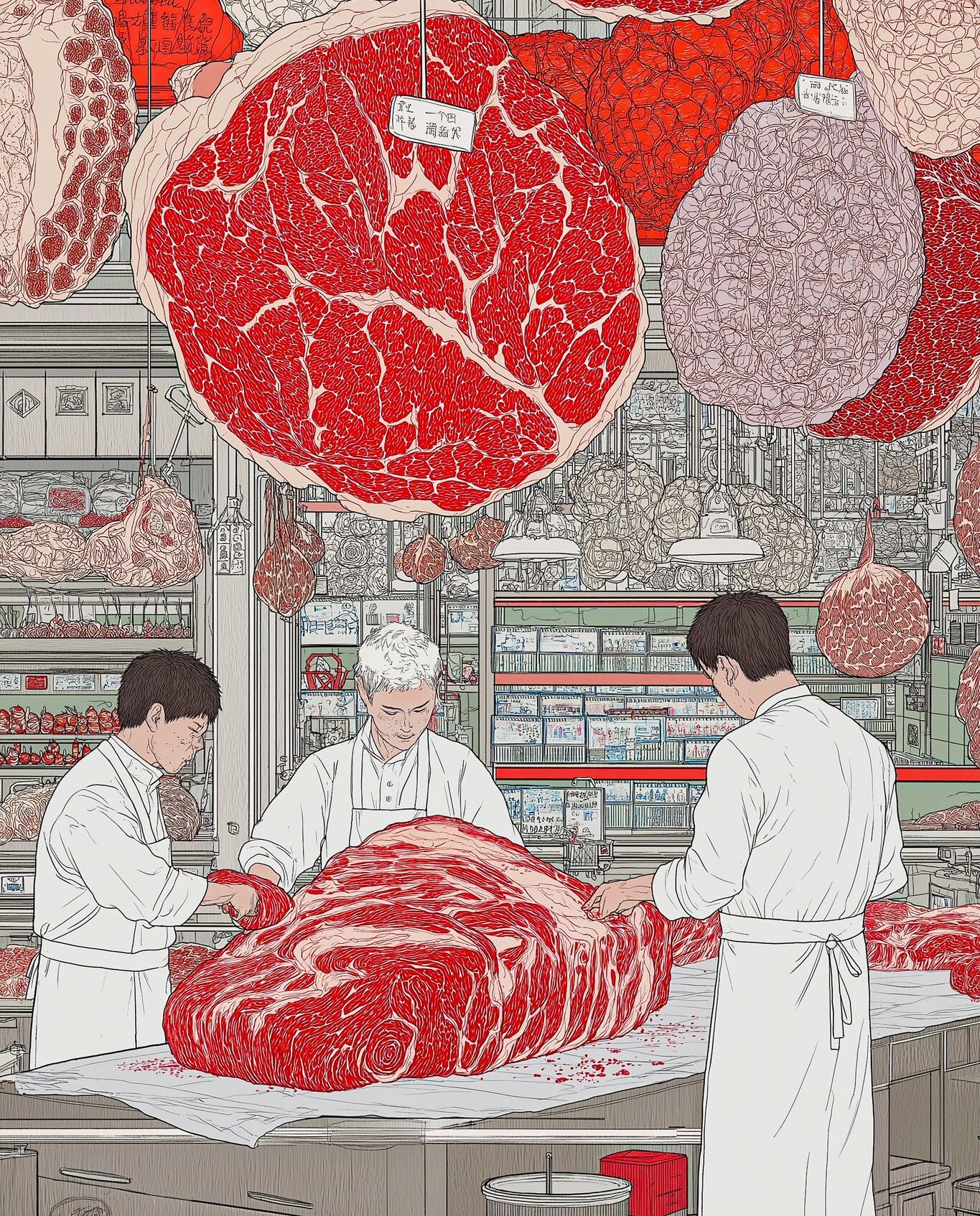

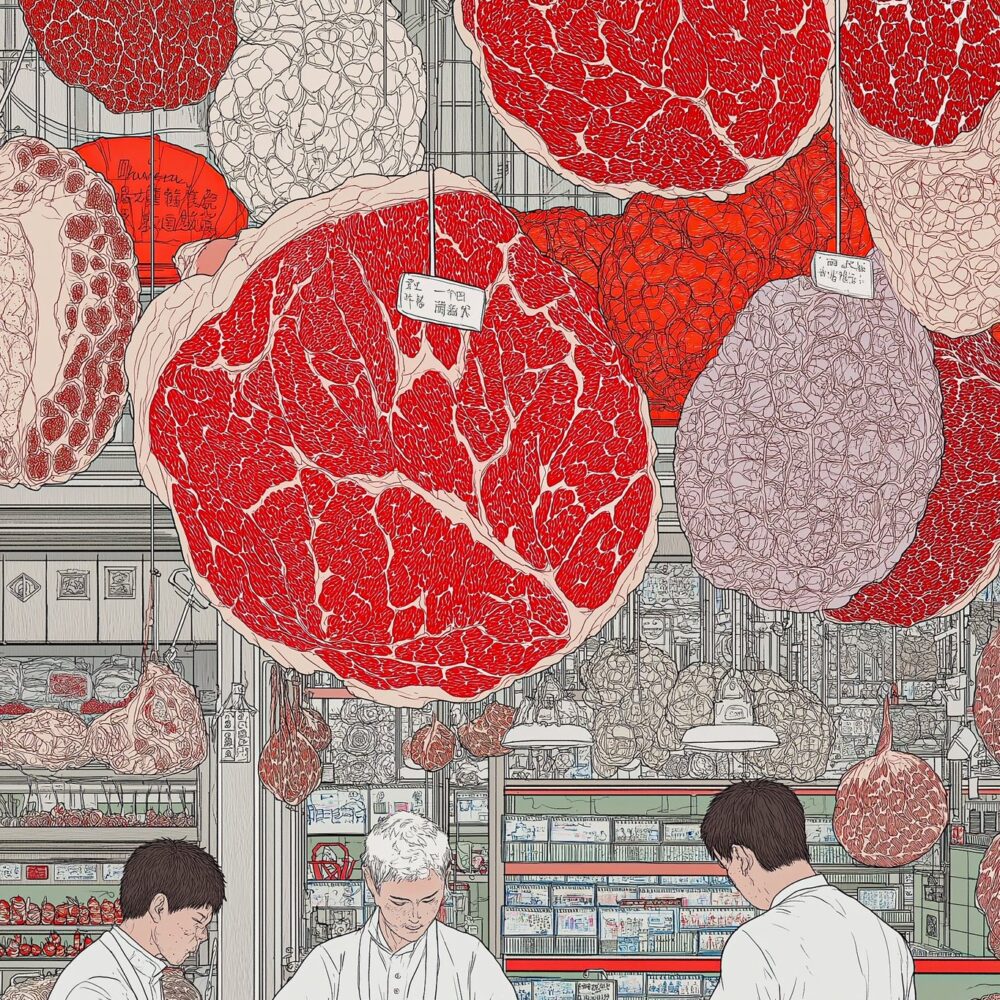

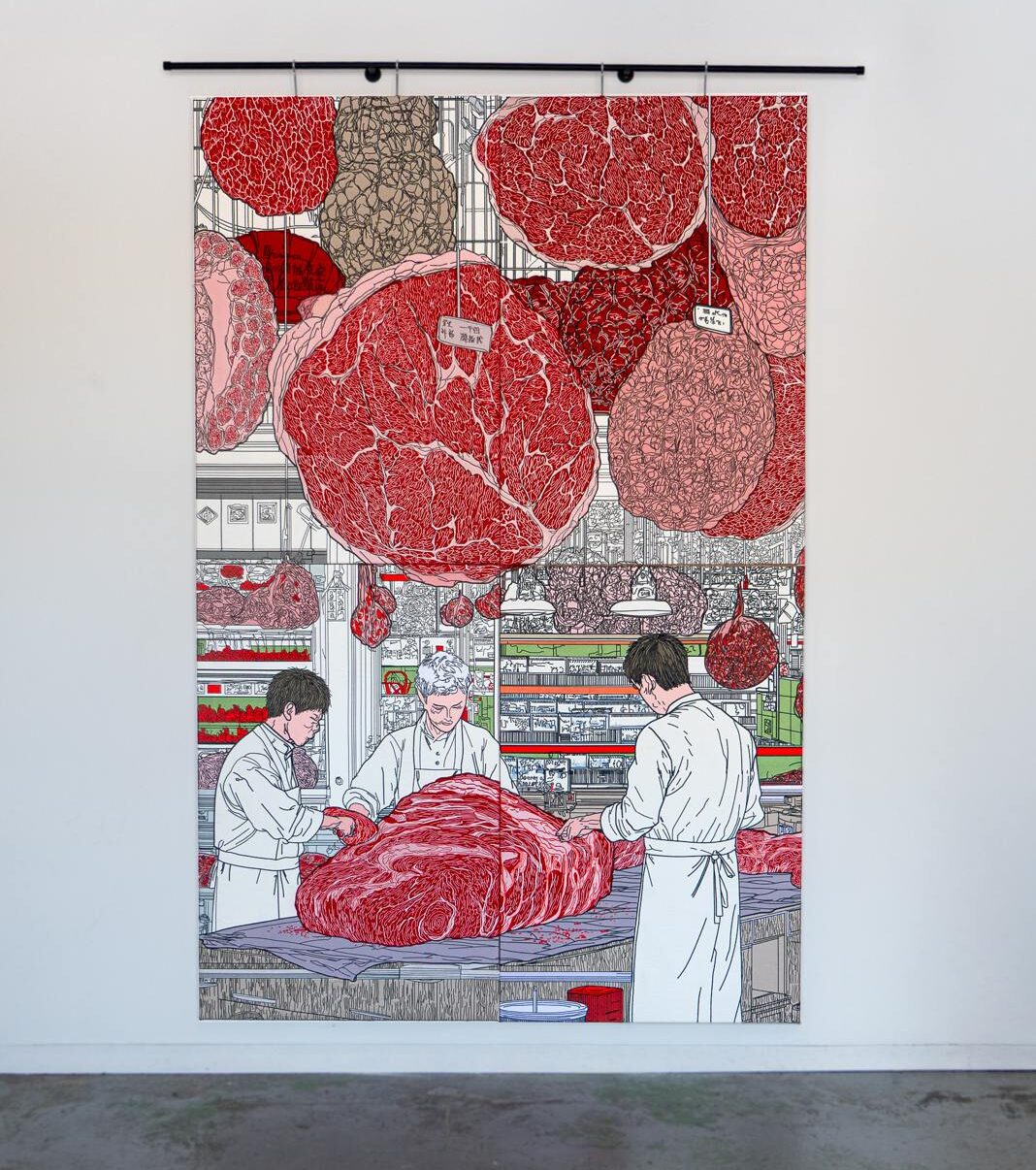

In Richard Nadler’s Sanctum Carnis (Latin for “Sanctuary of Flesh”), the artist threads together ancient ritual, industrial precision, and machine-driven aesthetics to create something both grotesque and reverent. The large-scale embroidered work—a towering 8.86 x 5.77 feet—depicts a butcher’s shop populated by suspended slabs of marbled beef, meticulously rendered in cotton yarn embroidery, robotically-produced from an AI-generated digital image. At once uncanny and familiar, the scene hovers between devotional icon and hyperreal parody, begging to be looked at, studied, consumed. But this is not just a butcher’s shop. It is a temple. And the object of worship is Wagyu.

Flesh as Devotion

In Sanctum Carnis, meat is sanctified. The red muscle and white marbling of premium Wagyu hang like relics above a gleaming altar. Three butchers—cloaked in white—surround a colossal cut of meat laid out before them like a sacred text. It recalls centuries of religious painting: triptychs, saints, martyrdom, sacrifice. One could mistake it for a lost panel of the Ghent Altarpiece, reinterpreted by a future obsessed not with salvation, but with consumption.

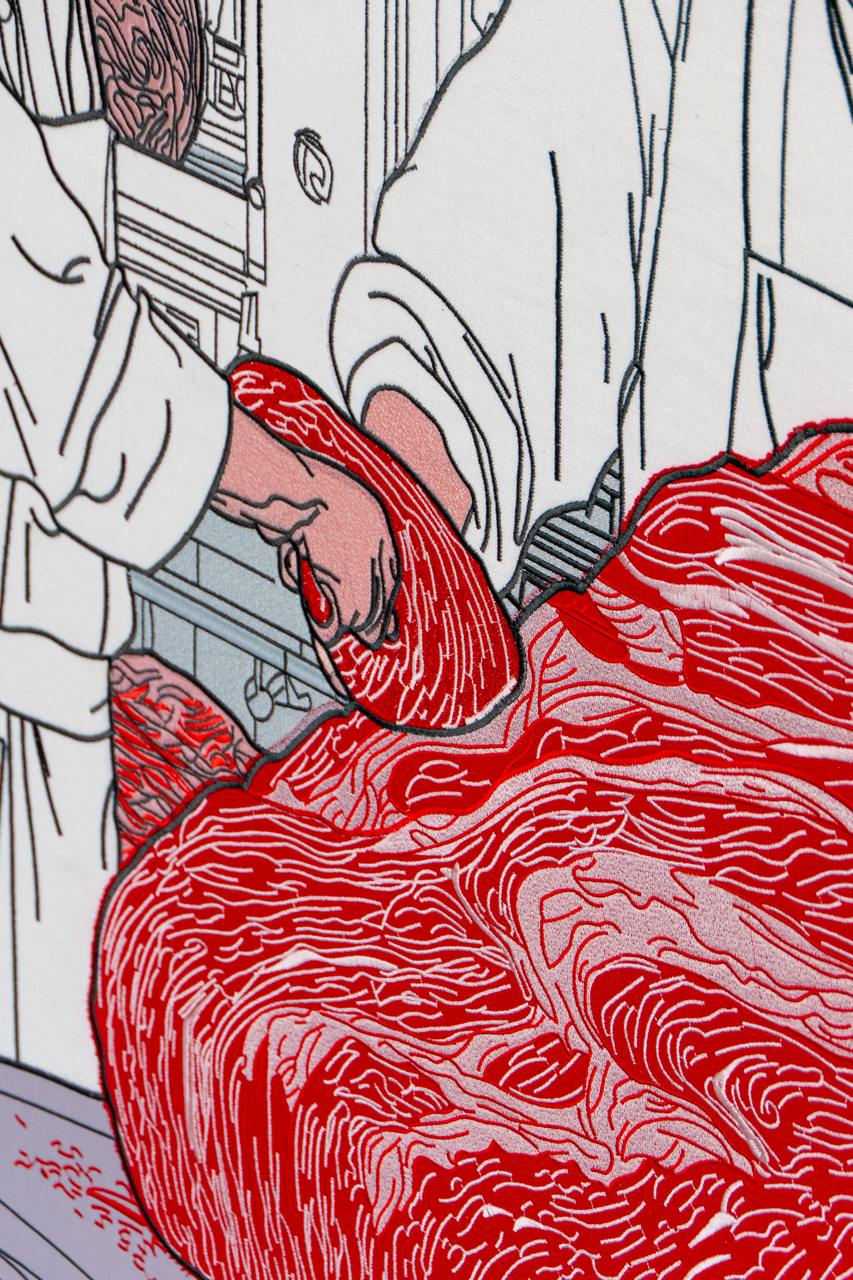

Nadler makes flesh a visual liturgy. In doing so, he blurs the divide between sustenance and spectacle, between body and commodity.

Tradition, Precision, and Technological Worship

The obsessive craftsmanship of Japanese Wagyu breeding—where cattle are massaged, tracked, documented, and cultivated with reverence—echoes in Nadler’s practice. Just as Wagyu is measured in grades of marbling and purity, Nadler uses a custom-trained AI model to process and abstract imagery until it achieves a perfectly ‘imperfect’ digital hallucination. The embroidery machine, guided by code, translates those signals into thread, one stitch at a time.

It is tradition executed through innovation.

Or perhaps innovation masquerading as tradition.

Here, technology doesn’t replace labor—it becomes it.

The AI imagines. The robot weaves. Nadler conducts. The resulting artifact is neither painting, nor textile, nor installation—but all three at once. A hybrid form that feels as precise as a diagram and as devotional as a shrine.

Consumption and the Market of Meaning

There’s an obvious resonance between the luxury food industry and the contemporary art world. Just as the elite line up for limited cuts of Wagyu, collectors and institutions compete for rare, hand-crafted, and technology-infused works like Sanctum Carnis. Both markets demand the exceptional—and fetishize process, scarcity, provenance.

And Nadler plays into that tension knowingly.

He renders the consumption of flesh not only literal, but symbolic.

Art, like meat, is an indulgence.

An object for taste. For desire. For power.

By reframing the butcher’s shop as a cathedral, Nadler gives us an image of contemporary value: the laborers working beneath slabs of status, the bodies consumed by the very systems they serve.

A Monument to the Machine-Flesh Era

In its material and message, Sanctum Carnis exists at a potent intersection: between the organic and synthetic, the sacred and commercial, the handcrafted and the algorithmic. It is a contemporary relic—stitched not by hand, but by machine; not imagined by man, but by model; and yet, unmistakably human in its urgency.

Nadler offers no judgment. He shows us the altar and lets us kneel.

As an artwork, Sanctum Carnis is a visual feast—meticulously rendered and conceptually layered. As a statement, it captures something urgent about this moment in history: our evolving relationship to tradition, technology, and taste. In that way, it belongs to a lineage of artists interrogating the systems that feed us—from the anatomical studies of Andreas Vesalius to the consumer critiques of Barbara Kruger. But where those dissect or deconstruct, Nadler enshrines.

He builds a sanctuary.

Of flesh. Of labor. Of machine.

And invites us in.