Noise, Memory, and Mutation: New Forms in AiR IV

In a digital landscape increasingly defined by speed, recursion, and entropy, AiR IV introduces three distinct voices who do not simply react to the environment around them but metabolize it, mutate it, and reflect it back with brutal, uncanny clarity. ADHD, cydr, and JULES, through their nine works created for AOTM's latest residency cohort, dismantle familiar frameworks and rebuild them into precarious new structures—half-remembrance, half-revelation. These artists transform noise into memory, and memory into mutation.

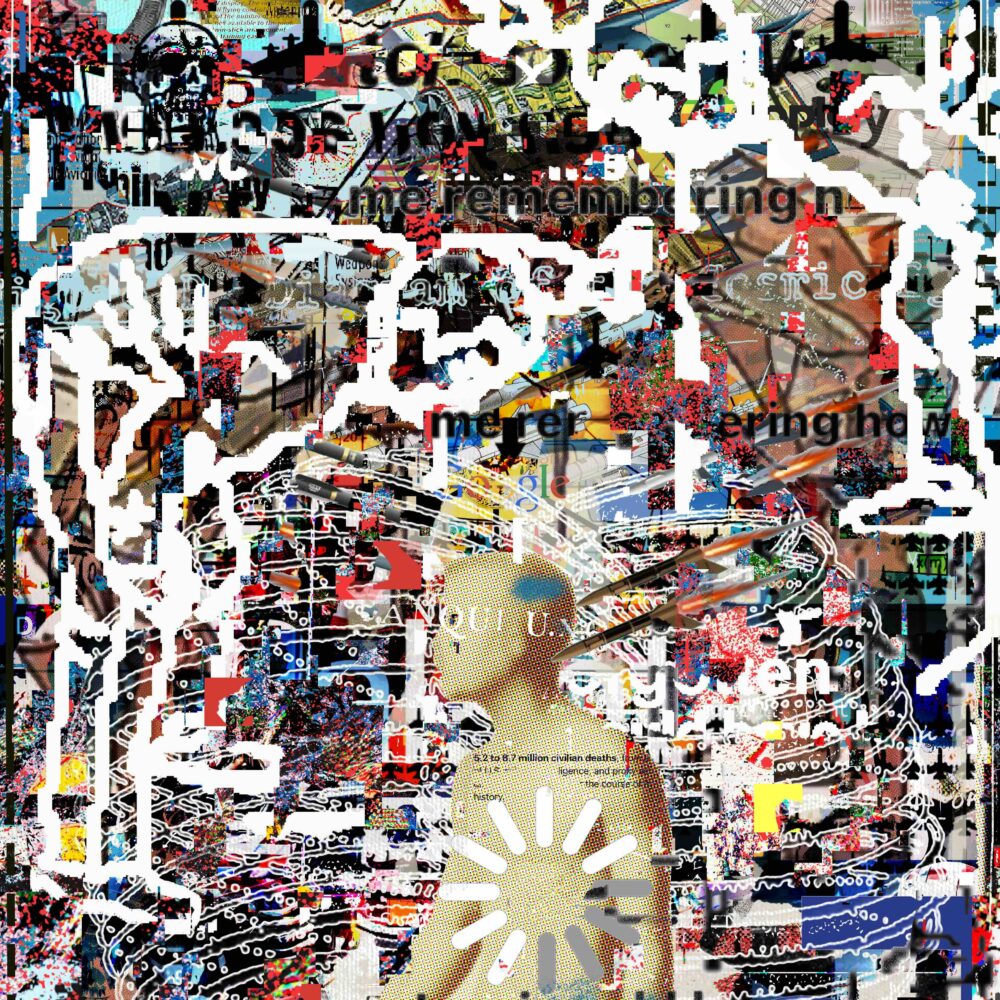

ADHD’s trilogy of digital collages — Me Remembering When I Could Have Forgotten, Failures Of Imagination, and Target Markets — reads like an archeology of a broken present. In Me Remembering When I Could Have Forgotten, a layering of corporate logos, fragments of pop culture, and references to U.S. military imperialism create a visual overwhelm that feels almost violently tactile. It echoes the silkscreen chaos of Robert Rauschenberg’s “Retroactive” series but with a contemporary fatalism—a world not just saturated by images, but wounded by them. ADHD’s interrogation of ChatGPT about war, civilian deaths, and the costs of empire is embedded beneath the image, transforming the piece from digital collage to ethical indictment. It’s not just media detritus—it’s a tombstone.

Failures Of Imagination continues this line of inquiry, focusing on the mythologies surrounding UFOs, UAPs, and military-industrial secrecy. The floating saucers—slick, diagrammatic, and fractured—recall the cold optimism of 20th-century futurism while exposing the collapse of consensus reality. The collage becomes a battleground where conspiracy, disillusionment, and true existential mystery collide. It’s no coincidence that the work evokes the palimpsestic layering of Jean-Michel Basquiat: both artists weave cultural noise into raw, accusatory myth.

In Target Markets, ADHD’s critique turns inward toward the architectures of surveillance capitalism. A gridded facial structure, tagged with emotional states and dollar signs, looms over a flurry of data points and corporate insignia. In some ways, it’s a digital descendant of Barbara Kruger’s didactic installations—”Your body is a battleground”—updated for an era where bodies are rendered as datasets. But ADHD’s work moves beyond appropriation: it theorizes the feedback loop between commerce, control, and emotional exhaustion. His “Inset” method—recursive layering of screenshots, glitches, and text—creates an aesthetic language of systemic failure.

Where ADHD confronts systemic collapse, cydr internalizes it, offering dreamlike visual reconstructions that shimmer between nostalgia and distortion. weatherman plunges the viewer into a mutable, almost biological landscape. Using digital collage and AI manipulation, cydr paints a world where color behaves like emotion—iridescent, mutable, fleeting. There’s an echo of Gerhard Richter’s “Abstrakte Bilder” here, but instead of oil paint, cydr uses the language of pixels and machine vision. weatherman is less about a literal storm and more about the storm of subjective experience—how moods migrate across our perceptual fields.

go, go, go! offers a rupture—a hyperactive, destabilized vision rooted in gaming culture. The viewer is dropped into a first-person shooter landscape, rendered strange and elastic through digital manipulation. It’s an homage to the overstimulation of the internet generation, yet also a melancholic critique. There’s something wounded in the pixelated corridors and blurred gunmetal—a nostalgia for intensity itself. Compared to the lucid dreamlike quality of weatherman, go, go, go! feels frenetic, desperate, a visual manifestation of what Baudrillard called “the ecstasy of communication.”

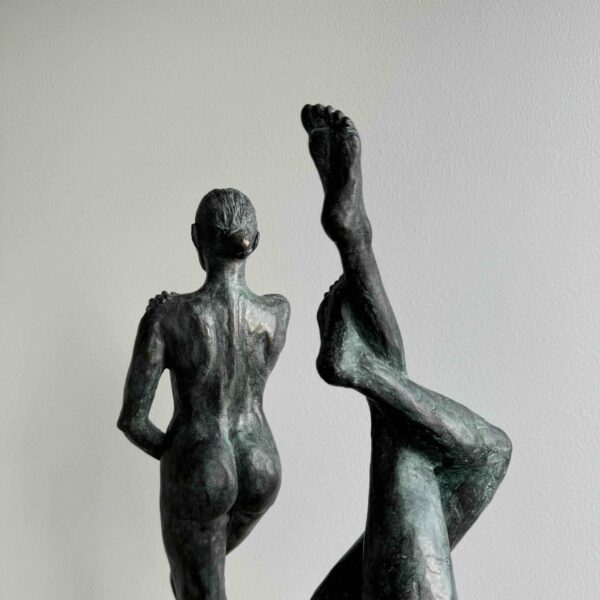

Sweet rewards, cydr’s final offering, is a vertical pilgrimage—a thin, fragile thread stretching skyward toward a dangling prize. The image, deliberately distorted and compressed, evokes a Sisyphean struggle toward fulfillment. It recalls the vertical aspirations seen in works by Yves Klein or Barnett Newman, but with a glitch-art twist. There’s a quiet violence in its slimness, a sense that transcendence is barely possible, and perhaps illusory. Here, cydr’s “Cydrism”—his playful refusal to define his aesthetic—feels most potent: a teasing of beauty from corrosion.

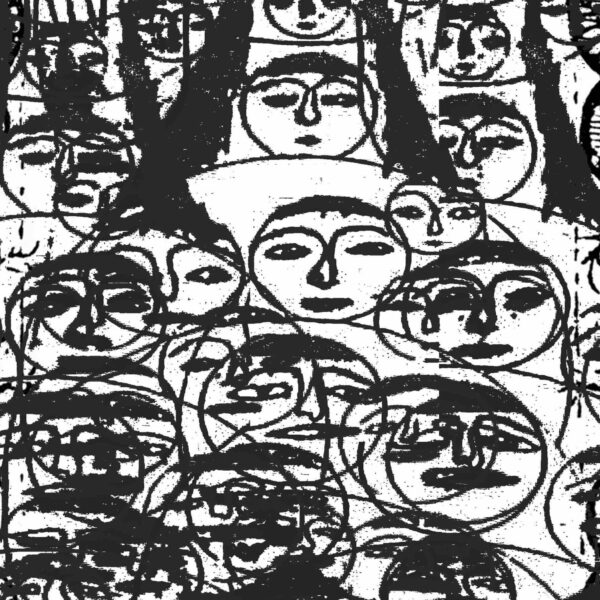

JULES, by contrast, brings a uniquely humanist sorrow to the digital space. How Are You Feeling Today? resurrects the old psychological charts of human emotions, but through a distorted, glitch-heavy lens. Each face—at once recognizable and alien—floats against blackness, a litany of affect stripped of certainty. Echoing Bruce Nauman’s “Clown Torture” or early video art’s obsession with human fragility, JULES captures the absurdity of trying to quantify inner life in a mechanized world. The use of simple blue text over the distorted faces drives home the question—can any of this be measured, controlled, sold back to us?

Places and Parts feels more haunted still: a body, reduced to flickering blue light, tumbles eternally through a digital void. It calls to mind Bill Viola’s early video installations or Nam June Paik’s meditations on transmission and decay. JULES’ manipulation of analog interference and digital fracture collapses the distinction between body and signal. It’s a work about vulnerability: the impossibility of holding oneself together in an era where even memory decays at broadband speed.

No Bell Bop offers perhaps the most elusive—and the most powerful—of JULES’ pieces. A fractured, thermal-esque portrait vibrates in neon against a black background. The title—a reference to the “I didn’t hear no bell” trope—suggests resilience in the face of defeat. In this image, joy and exhaustion coexist: the figure both triumphs and disintegrates. Like Alvin Lucier’s “I Am Sitting in a Room,” which records a voice until only resonance remains, No Bell Bop captures identity as something vibrated into abstraction, surviving even as it unravels.

Together, ADHD, cydr, and JULES do not simply mirror the collapse of coherent narratives; they transform it. They propose new strategies for art in an age of saturation and decay: strategies of excavation, mutation, and re-enchantment. They echo—and expand upon—movements like the Pictures Generation and New Media Art but with an urgency specific to a generation that has never lived outside the digital slipstream.

What distinguishes this cohort is not merely their technical skill or their conceptual rigor, but their willingness to work inside the wound. They do not retreat into nostalgia, nor do they preach empty techno-utopianism. Instead, they insist on staying with the trouble, to borrow Donna Haraway’s phrase—wading deeper into the incoherence of now in search of new forms of meaning, however fragile.

AiR IV is not a showcase of polished optimism. It is a field report from the fractured psyche of the present moment, delivered through the glitching light of our collective memory. It is a reminder that even in collapse, something beautiful—something true—can emerge: not a monument, but a murmuration, alive and mutating and infinitely unfinished.