Jack Butcher’s Visual Eloquence: Simplifying Complexity

We had the opportunity to speak with Jack Butcher, an artist and graphic designer whose style is deeply inspired by his personal artistic journey. After many successful years working in Fortune 100 advertising as a graphic designer, he forged his own path as an artist using the power of social media to build his digital network. Thus, he built Visualize Value, a media platform of his own. In this interview, we dive into Jack’s inspiration, his penchant for taking chances, and his search for creative freedom. Please note, this conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: What is your first memory of liking and enjoying art? Tell me a little bit about your childhood, getting into art, and what that process was like for you.

BUTCHER: Surprisingly enough, I don’t think I was really around art at all as a kid. I think design was where I first got my creative itch scratched. My dad is an engineer and he had a workshop at the house where he was constantly working on projects. I was hanging around in there a lot, looking over his shoulder as he was building things, designing things, and fixing little problems. It was always interesting to me. I only studied art as a young kid as part of the public school curriculum. I never really thought of myself as being even particularly good or interested in it earlier in my life. It didn’t click for me until much later.

Q: When did it click for you? What was the catalyst?

BUTCHER: I graduated from school and found myself working as a client service executive for a commercial printing company. One of their clients was this magazine called Graphic, which was an incredibly well-designed magazine with 50 different paper stocks and different finishes. It was essentially a monthly compilation of work from the world of graphic design. That’s the thing I retroactively attribute to getting interested in design as a discipline professionally at least.

I was looking at this magazine thinking, what am I doing here? Somebody somewhere is working on the things that are being put into this magazine, I need to figure out how I get into that world.

Q: How did you make the transition from client services to creating art yourself?

BUTCHER: I decided to go and study graphic design. I somehow backed my way into a university course to study design without any formal training or a portfolio of work. I would come home from work and just make stuff on the computer. I put that in my portfolio and applied to design school. As soon as I got out of school, I tried to get any kind of design experience I could. Eventually, I got this unpaid internship in London, working for this little design studio called Underdog. I was doing a lot of web design and a little bit of branding work. There were a couple of people who worked there who, I remember just looking at what they were doing, and thinking – these guys are so insanely talented. It was mind-bending to me. The stuff they were making, it is incredible that somebody can sit in front of a computer and produce that.

Q: How did you create that link from your education into the world of graphic design?

BUTCHER: Well, that’s a weird chapter of the story. I was working this internship in London and I was commuting from my hometown. It was four hours of commuting every day. I went to the pub one night and I met these guys, these friends of friends, who were going to New York through a connection they had at Virgin Atlantic. Somebody got cheap tickets to New York and they had one spare ticket. I was like, alright, I’ll go. I never did any traveling before that point, so I was trying to catch up on the life experience front. I figured that the design industry in New York’s got to be one of the best in the world, so I should try and meet people while I’m there and not just turn this into a pure vacation. I was going for three months, and before I went, I sent probably 150 emails.

Q: Did you end up with a job from that emailing rampage?

BUTCHER: Well, I got one response from a guy who, after doing 20 years in advertising on Madison Avenue, was starting his own agency in West Chelsea. It was called Exit. I attached a PDF to the email and said, “I’m coming over to New York for three months. I’d love to just be able to come in and see how you work and what you’re up to and stuff like that.” That was when I first dove into full-time design work. I ended up getting a visa and working there for a couple of years. I was thrown into the deep end of the New York agency business. After that, I just sort of moved around the agency scene in New York. After that for close to 10 years, I probably had 12 jobs or something. I would land at a place, do something for six months, nine months, get a little bit bored and then think, oh, I’ll just go to another agency that’ll be different or better. It was just always the same work, and I’d run into the same frustrations.

Q: What kind of work were you doing for these agencies?

BUTCHER: At first, I did all sorts of different commercial design stuff. When I first started, a lot of it was super traditional advertising stuff, print ads in-store stuff, billboards, and all sorts of traditional applications of graphic design I guess you could call it. My job title was graphic designer, but it eventually became art director. I would work from conception to production of advertising campaigns, brand identities, website designs, and eventually digital products. Every job got me closer and closer to digital-only design. I guess that was a function of how the world was changing too at the time.

Q: Can you tell me a little bit more about that moment of transition from working at the agencies to exploring more of your creative freedom? Was there a specific straw that broke the camel’s back?

BUTCHER: Yeah, so, at the end of my W2 career, I was working back at a small-ish agency, like a couple hundred people, which is small compared to the 15,000-person staff of one the bigger agencies I worked at. That’s one of the sweet spots of the agency world – these nimble, small agencies where you do get to be very creative, and you can lead the work, and there’s not that much bureaucracy to cut through to make great stuff. At the same time, you do get to the point where politics are part of your job. The politics overtake the production of the work, or the craft of the design. I think that’s where I just started to get a little frustrated that I didn’t feel like I was doing what I was supposed to be doing. And honestly, some of the things that you work on are just very uninspiring.

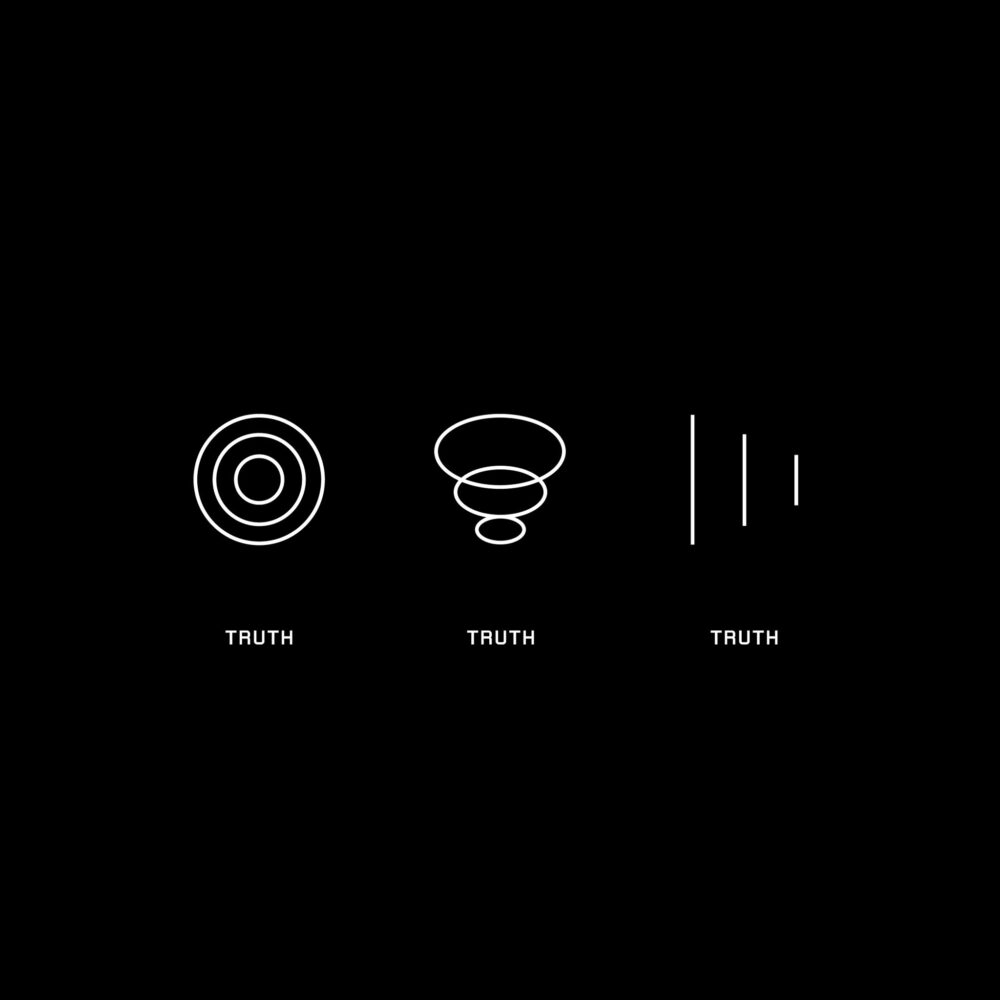

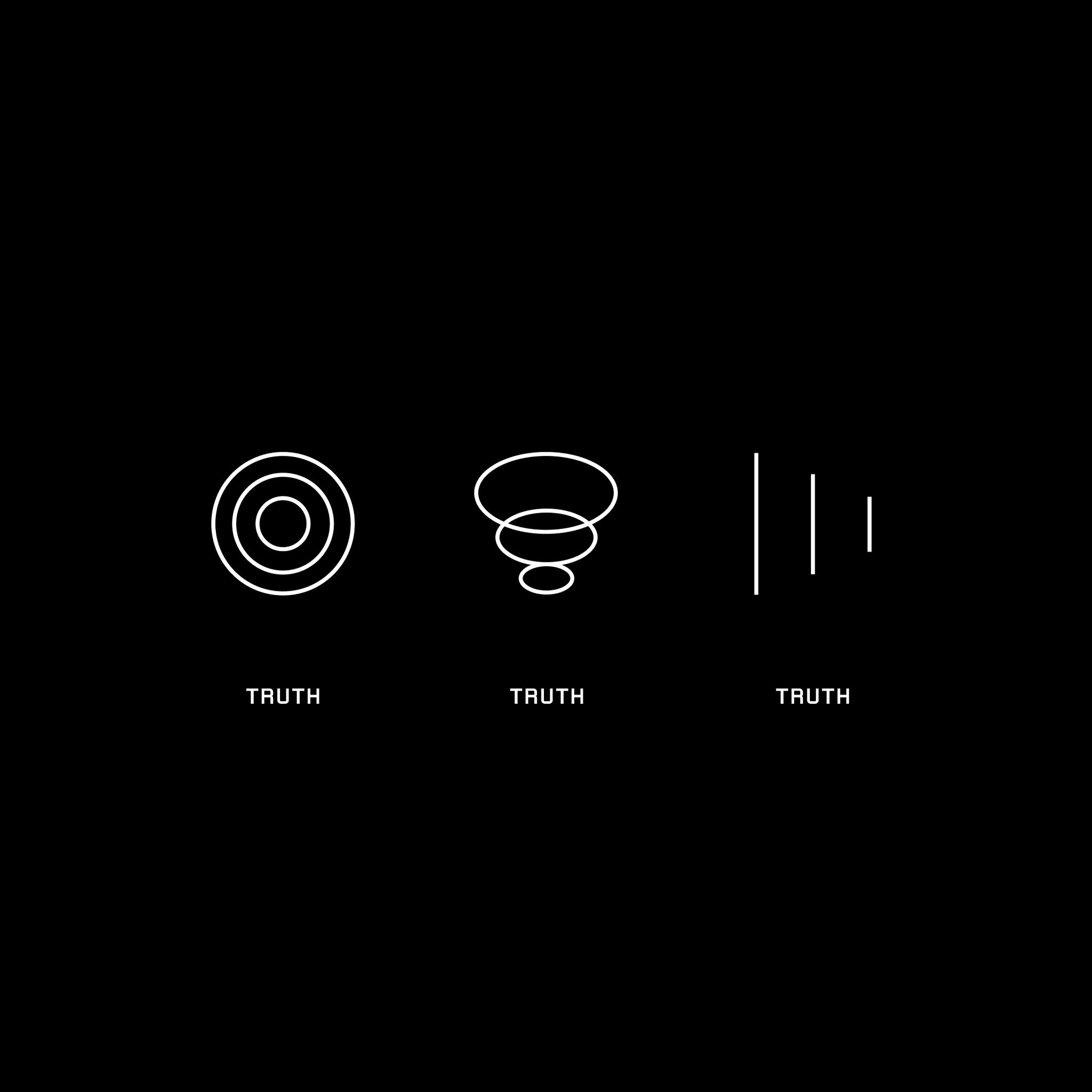

I think reducing something to its absolute visual essence is the objective.

Q: Was there a specific straw that broke the camel’s back?

BUTCHER: It becomes so much red tape, that all the incentives are out of whack. The agency is trying to take as long as possible, and the client is trying to take as few risks as possible. So you’re just sort of stuck in this limbo. There are so many talented people in that environment who are unable to get their ideas out in the world because of that. The way that industry operates, with a lot of the work you create, can’t even show. With some projects, you sign NDAs on the work you’ve done that lasts for 10 years. So the agency owns your creative output, which is also a brutal reality to face when you’re trying to look at what you have to show for the work you’ve done. So loads of overlapping reasons why I got frustrated with that environment that led me to start my own thing.

Q: For someone who’s never seen your work before, can you talk a little bit about what it looks like? How would you describe your style?

BUTCHER: I’ll try. I’ll try. I think the funny thing is that it’s best explained by looking at it, but if I were to attempt to describe it with words, I think reducing something to its absolute visual essence is the objective. More often than not, looking at ideas through that lens filters for ideas that make sense, or have some logical structure to them. If I saw something that I felt had a structure that could be converted to this simple set of constraints – the canvas is black, a specific typeface, deciding to use shapes or vector outlines, etc, I would start from there. There are no creative elements beyond that. My work forces creativity to flow through an idea, rather than the stylistic decisions that you’re making. That system helped me get better at conveying ideas.