Fragmentation, Temporality, and Digital Perception in Goyong’s Artistic Practice

Goyong’s digital artwork explores the intersection of technology, nature, and human experience, drawing from his foundational background in sculpture and expanding it into the digital realm. His practice transforms traditional notions of abstraction, offering a reflection of our fragmented and increasingly mediated existence. In works like City, The Flowers, No One at Home, and Seoul, Goyong blends the tangible and the transient, utilizing pixelation as a method to evoke a sense of temporal fragility. In many ways, his pieces challenge the boundaries of traditional art forms while engaging with the ephemeral nature of modern life, evoking the influence of major art historical figures, from modernism to postmodernism. This essay examines the artist's practice through the lens of his use of abstraction, digital media, and the exploration of contemporary realities.

City: Urban Fragmentation in Digital Abstraction

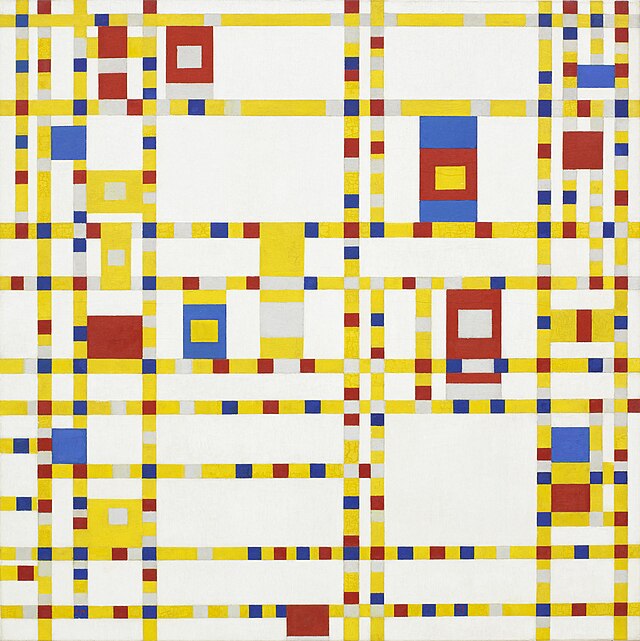

Goyong’s City is a striking example of how he translates urban life into fragmented, pixelated abstraction. The work’s digital representation of a cityscape recalls the formalist approaches of modernist artists like Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich. Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942), with its geometric abstraction of the New York City skyline, and Malevich’s Black Square (1915), with its reduction of form to essential geometric shapes, both sought to capture the essence of modernity through abstraction. Similarly, City abstracts the urban environment through a pixelated grid of colors, distilling the complexity of the city into visual elements that reflect the speed, the chaos, and the uniformity of modern life.

However, where Mondrian and Malevich utilized simple geometry to represent the modern world, Goyong’s work uses digital tools to fragment and distort this landscape. The pixelated nature of the piece speaks to the disconnection of the digital age, where city life—once experienced in its full sensory detail—is now mediated through screens and pixels. This mediation of reality recalls the ways in which our daily interactions with the city are increasingly mediated by technology. The city in City is a digital simulation, a hyperreal version of itself, where the line between the actual and the simulated is blurred, much like the theory of hyperreality outlined by Jean Baudrillard.

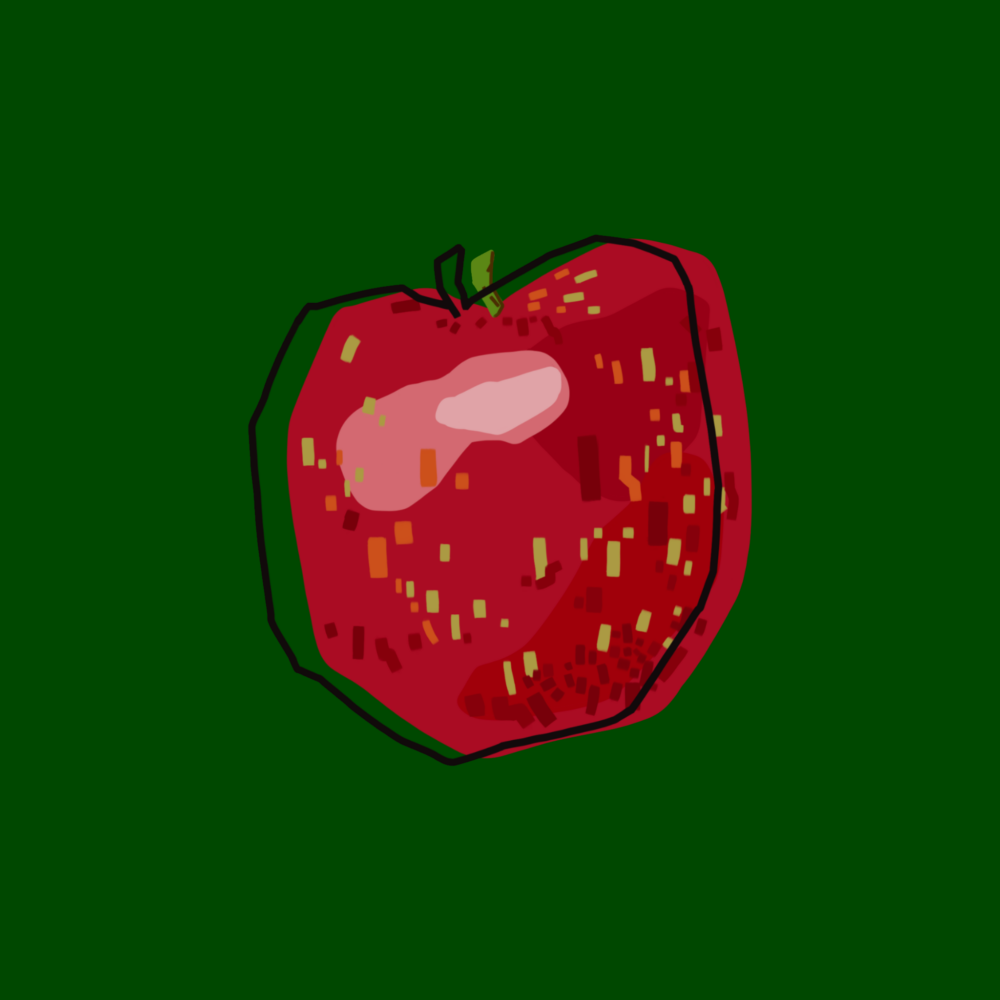

The Flowers: Nature in the Age of Simulacra

In The Flowers, Goyong takes us into a more intimate, yet similarly fragmented, world of digital nature. Here, a seemingly realistic flower painting becomes the site of a digital illusion where butterflies are drawn to the painting for its splendor, but soon abandon it once they realize it cannot provide the scent of a real flower. This work resonates with Andy Warhol’s approach to mass production and artifice in his Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). Warhol’s use of familiar objects, stripped of their emotional or cultural significance, challenges the viewer’s attachment to “authentic” representations of reality. Likewise, Goyong’s flowers, while visually captivating, lack the sensory depth of a real flower, prompting viewers to question what constitutes the “real” in a digitally mediated world.

The story of the butterflies, who are drawn to the painted flowers yet eventually leave, reflects a deeper critique of the illusions technology creates. The flower is not a real, living organism but a simulacrum—something that imitates nature without truly embodying it. Goyong’s work, much like Warhol’s, points to the tension between appearances and reality, highlighting the ways digital representations challenge our perceptions of authenticity. Here, the simulated beauty of the flower painting speaks to the broader theme of digital art’s role in distorting and fragmenting the natural world, pushing us to reconsider what is “real” and what is manufactured.

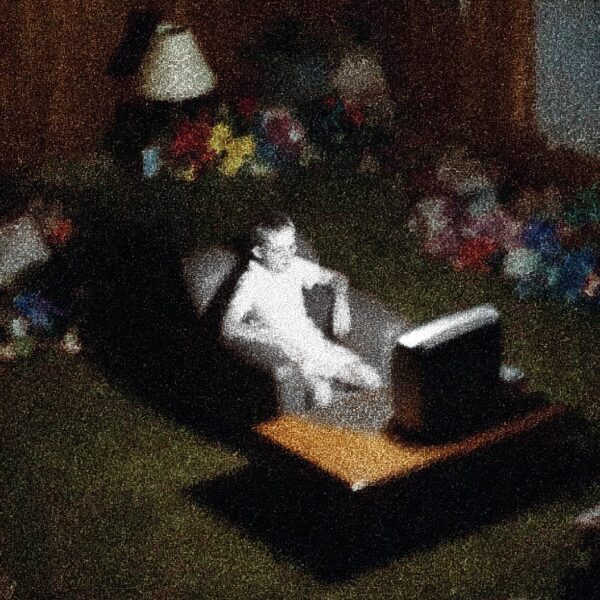

No One at Home: Domesticity Through the Lens of Digital Abstraction

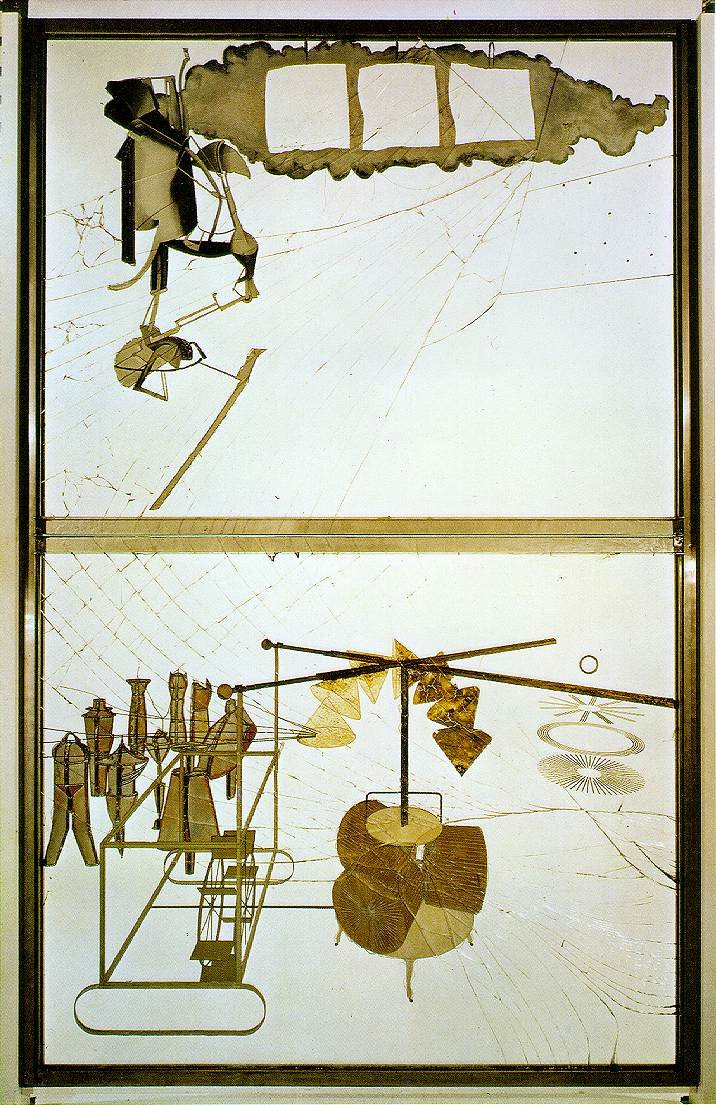

No One at Home takes on a domestic scene, with pixelated objects scattered across a fragmented living room. This work recalls Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915), where the mundane and the domestic are transformed into abstract, complex constructions. Duchamp’s fragmented view of everyday objects was a challenge to the viewer’s understanding of reality, and Goyong similarly uses pixelation to distort the familiar. The scene is simultaneously recognizably domestic and utterly abstracted, leaving the viewer with a sense of disorientation.

Like Duchamp’s work, Goyong’s scene invites contemplation about the way everyday objects are represented—and how these representations are increasingly mediated by technology. The disjointedness of the image hints at the alienation that comes with our digital engagement with the world. The objects in the room, once familiar, are now reduced to abstractions, questioning our perception of space, materiality, and intimacy in an age where technology governs the way we relate to the world around us. Goyong’s use of digital abstraction, much like Duchamp’s, challenges us to question what we consider “real” and how our understanding of the everyday has been irrevocably altered by technology.

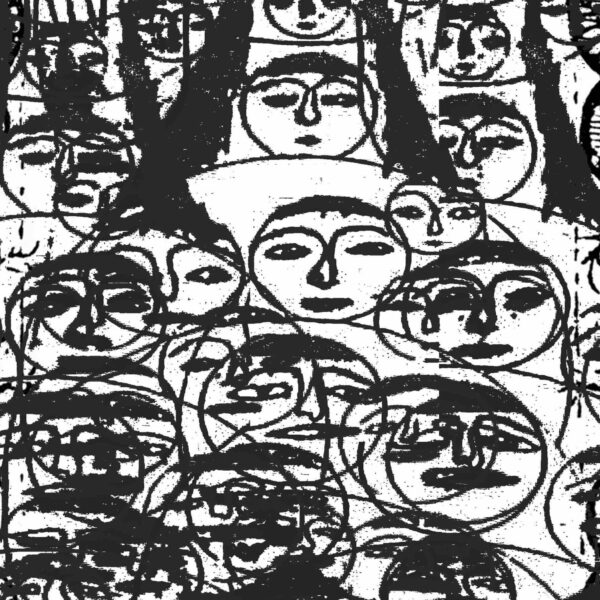

Seoul: The Hyperreal Cityscape

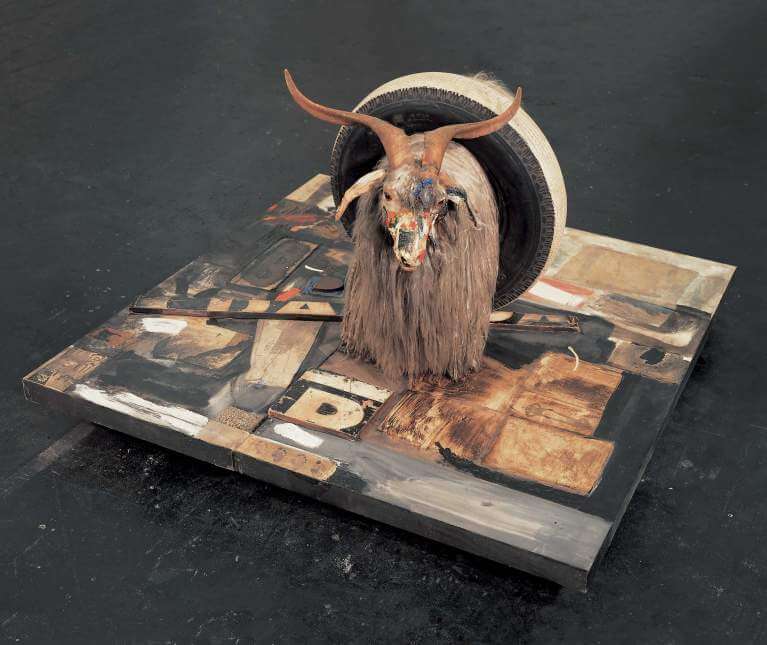

In Seoul, Goyong portrays a busy, bustling cityscape, creating a pixelated vision of South Korea’s capital, a center of finance and politics. The work is not just a depiction of a city but an abstracted version of the lived experience within it. This reflects Robert Rauschenberg’s approach to blending everyday life and abstraction in works like Monogram (1955), where the mundane and the extraordinary coexist. Rauschenberg’s combines, which often incorporated found objects, challenged the distinctions between high and low culture, just as Goyong’s digital cityscape blurs the line between the real and the virtual.

The city depicted in Seoul is fragmented and pixelated, evoking a sense of disconnection from the real city it represents. The digital abstraction that permeates the work emphasizes the disconnect between our lived experience and the representation of that experience through digital screens. Goyong’s use of pixels and color to depict a city reflects the role of technology in shaping how we perceive urban spaces. The fragmented pixels become a metaphor for the fragmented nature of contemporary life, where the overwhelming demands of the digital age shape how we experience and engage with the world around us.

Digital Abstraction and Fragmentation in Goyong’s Work

Goyong’s art is an exploration of the fractured, mediated nature of modern existence. Through digital abstraction, he navigates the tension between the real and the simulated, capturing the fleeting and fragmented moments that define contemporary life. Drawing inspiration from the modernist tradition, from Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich to Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, Goyong uses digital tools to reimagine the themes of abstraction, identity, and perception. His work continues the legacy of abstraction but introduces a modern sensibility, one that reflects our increasingly digital and mediated world. By engaging with nature, domestic life, and urban landscapes, Goyong’s work redefines how we understand our surroundings in the age of digital representation. His digital abstractions remind us that our engagement with the world is increasingly filtered through screens, creating new possibilities for how art can capture the complexities of modern life.