Batzdu’s Digital Neoplasticism: The Meme as an Artistic Absolute

Art history, particularly the modernist era, was shaped by a deep desire to refine and reduce—whether it was Cubism dissecting reality into fractured planes, De Stijl seeking an absolute aesthetic order, or Conceptual Art relinquishing the hand of the artist altogether. In contrast, the internet is an engine of proliferation, acceleration, and fragmentation, where meaning is rarely fixed and the aesthetic is shaped less by an artist’s singular vision and more by collective reinterpretation. This paradox sits at the core of Batzdu’s work. Batzdu does not simply appropriate modernist visual language; he reconfigures it through what he terms “Modern Memeism.” His four works—Curiosity, Pepedenza #2, Meme #96, and GeoMetric Pepe #52—each engage with a different strain of 20th-century abstraction, only to subvert, repurpose, and embed it within the chaotic recursion of meme culture. What emerges is not a nostalgic pastiche of modernist ideals, but a mutation of them—an acknowledgment that digital culture does not merely inherit the past but digests and remixes it into something entirely new.

Curiosity and the Cubist Fragmentation of Knowledge

The earliest visual precedent for Curiosity is Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 20th century. Cubism sought to challenge traditional notions of perspective by fracturing objects into multiple viewpoints at once. This was radical in its time because it rejected the illusionistic realism that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. Instead, it suggested that no single perspective could fully capture an object’s true nature—an idea that resonates profoundly in an era oversaturated with competing digital narratives.

Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) marked the birth of Cubism, portraying five angular, mask-like female figures that seem both rigid and fluid, familiar and alien. Similarly, Batzdu’s Curiosity (2023) presents a deconstructed human form—hands, limbs, and a mask-like face interlocking in an uneasy composition. However, where Cubism was concerned with perception and form, Curiosity operates in the realm of semiotic uncertainty. The interrogative title—What? When? Why? Where? How?—suggests an epistemological crisis, much like the way internet culture constantly recontextualizes and distorts information. The sharp, synthetic quality of Batzdu’s digital rendering further distances it from Picasso’s earthy brushwork, reinforcing the shift from material to meme, from hand to algorithm.

Pepedenza #2: From Futurist Dynamism to Semiotic Disintegration

While Curiosity nods toward Cubism, Pepedenza #2 (2023) bears an unmistakable kinship to Italian Futurism, particularly the fragmented energy of Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913). The Futurists, led by figures like Boccioni and Giacomo Balla, sought to capture speed, technology, and the mechanization of human experience. They believed that traditional art was stagnant and that the future belonged to dynamic, abstracted motion.

However, Batzdu does not adopt Futurism’s bombastic optimism. Instead, he applies its visual logic to a world where symbols, rather than bodies, are in constant motion. Pepedenza #2 disassembles national colors and iconography into curved, shifting fragments, hinting at flags but never fully resolving into recognizable forms. This recalls Balla’s Abstract Speed + Sound (1913–14), where color and shape blur into a sensation of velocity. But where Balla was capturing the excitement of a world in rapid change, Batzdu portrays the disintegration of stable meaning itself. In an age where online discourse is saturated with ideological co-opting and symbolic warfare, Pepedenza #2 reads like an abstraction of memetic propaganda—national identity reduced to a customizable, interchangeable visual language.

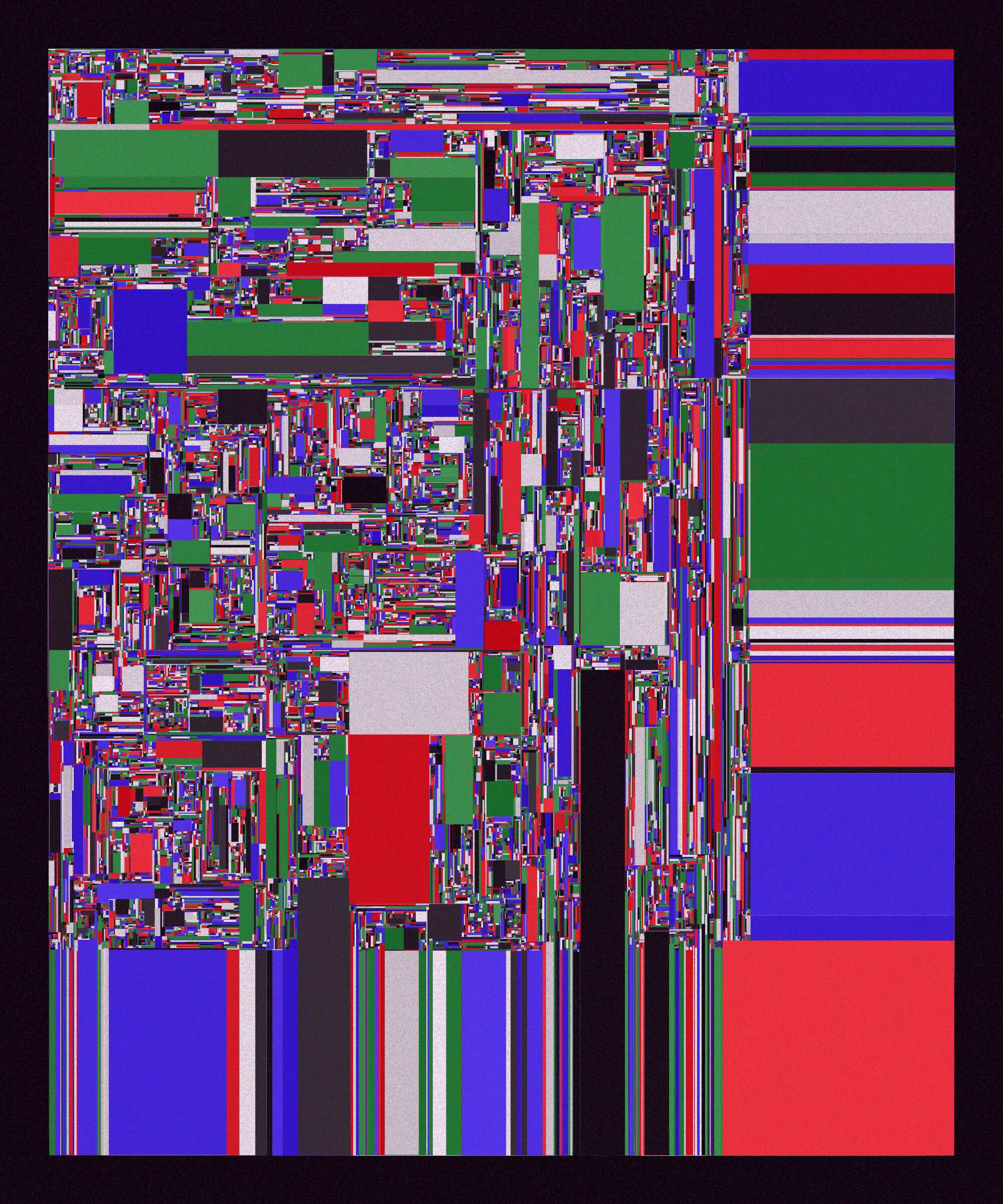

Meme #96: The Glitching of Mondrian and the Algorithmic Sublime

If Curiosity and Pepedenza #2 examined fragmentation, Meme #96 (2024) shifts toward recursion—symbols breaking down into smaller, self-replicating units, much like internet memes themselves. Here, Batzdu’s clearest visual touchpoint is Piet Mondrian, whose geometric compositions aimed to strip art of subjectivity, leaving only pure relationships of color and form.

Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1921) was an attempt to create a universal, harmonious aesthetic—one that eschewed narrative and representation in favor of absolute abstraction. Meme #96, however, takes Mondrian’s grid and distorts it beyond recognition. The clean divisions of De Stijl dissolve into a chaotic field of glitching, pixelated blocks, invoking the visual language of compression artifacts and corrupted data. This brings Batzdu into dialogue with glitch artists like Rosa Menkman, who argue that digital distortion is not merely an error but an aesthetic condition of contemporary existence.

In this sense, Meme #96 functions as a critique of both Mondrian’s utopian purity and the contemporary internet’s insatiable churn of visual culture. If Mondrian sought to “destroy these lines” to reach an ultimate artistic truth, as Batzdu’s accompanying text playfully references, then Meme #96 suggests that the grid has already collapsed under the weight of infinite digital reproduction.

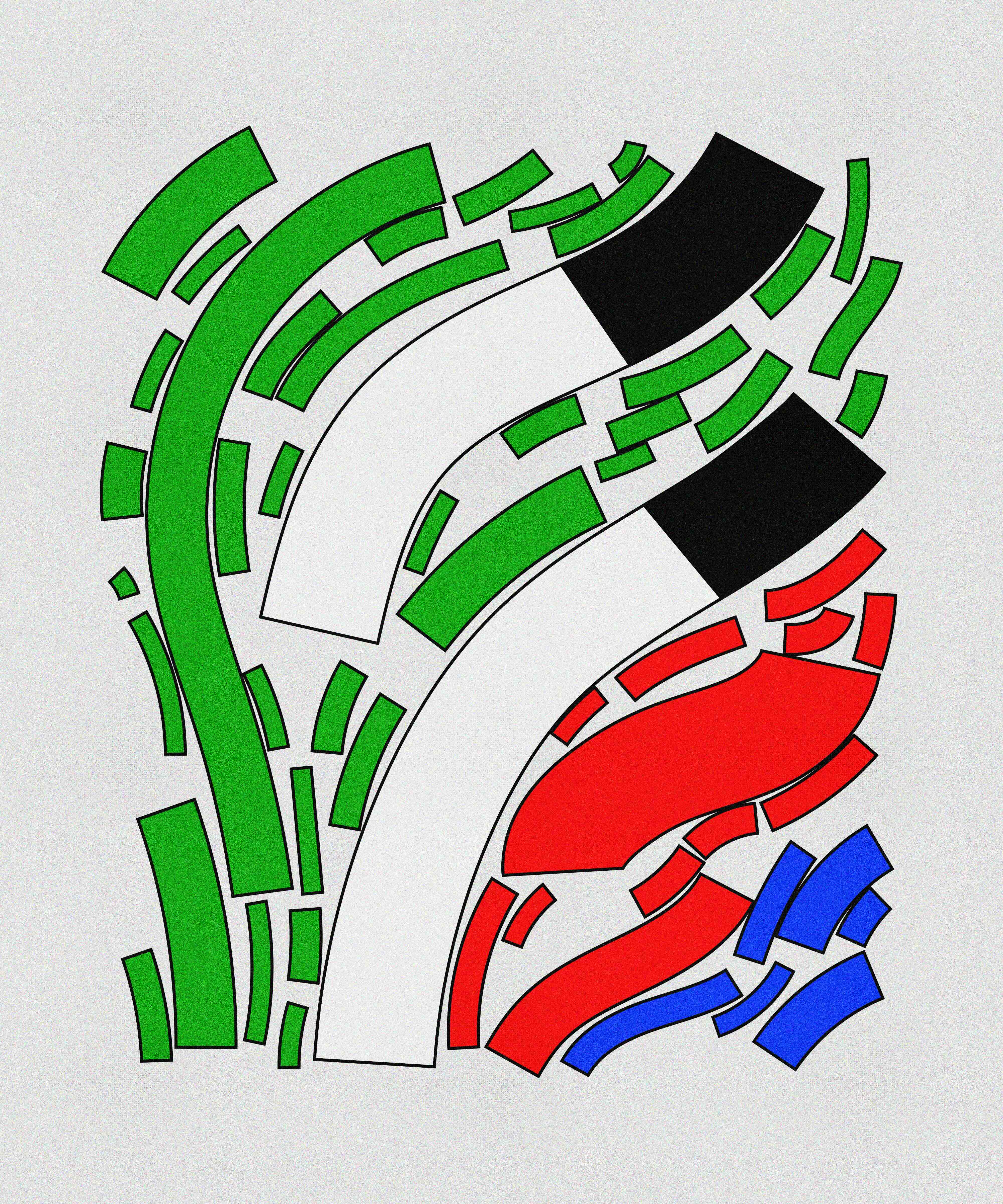

GeoMetric Pepe #52: The Memeplex Consumes Modernism

The final piece, GeoMetric Pepe #52 (2022), offers the most direct confrontation with modernist ideals. It does not merely reference Mondrian—it hijacks him. Here, Pepe, the endlessly reinterpreted and politically co-opted meme, is embedded within a rigid Neoplasticist grid. The piece cheekily suggests an alternate history where Mondrian’s pursuit of universal abstraction was never realized; instead, the memeplex infiltrated and rewrote it.

This work operates in a lineage of pop artists who subverted modernist ideals, such as Roy Lichtenstein’s Look Mickey (1961), which reimagined highbrow Abstract Expressionist brushwork as a mass-produced comic book aesthetic. But while Lichtenstein’s critique was tied to consumer culture, Batzdu’s is uniquely postmodern: his work does not simply parody Mondrian—it suggests that the memeplex has become the dominant aesthetic force of our time.

Where Mondrian sought order, Batzdu finds playful chaos. Where De Stijl sought an escape from representation, GeoMetric Pepe #52 revels in its inevitability. In doing so, Batzdu delivers a fundamental truth about art in the digital age: there is no longer an avant-garde to push forward—only an infinite loop of mutation, propagation, and recombination.

Modern Memeism: A New Aesthetic Paradigm?

With these four works, Batzdu proposes an alternative to modernist teleology. His “Modern Memeism” is not about refining form to a purer state, as Mondrian and Malevich aspired to, nor is it about the utopian embrace of technology that characterized Futurism. Instead, it acknowledges the instability of meaning, the fragmentation of identity, and the inevitability of cultural remixing in a hyperconnected world.

By embedding memes into the visual grammar of modernism, Batzdu does not elevate them; rather, he suggests that they have already supplanted traditional art historical narratives. The question is no longer whether memes can be art, but whether art can exist outside of the memeplex. And if it cannot, then what comes next?

Batzdu’s work does not offer an answer—only a mirror, infinitely refracted.